Online terrorist activity a growing concern in Sahel region

For terrorists, the Internet is a double-edged sword. One one hand, online communication – so instant and far reaching – eases the flow of dissent. At the same time, governments and security forces have a new means to intercept illicit transmissions. Such is the game of cat-and-mouse in Africa as broadband and mobile service arrive in rural areas across the Maghreb and Sahel.

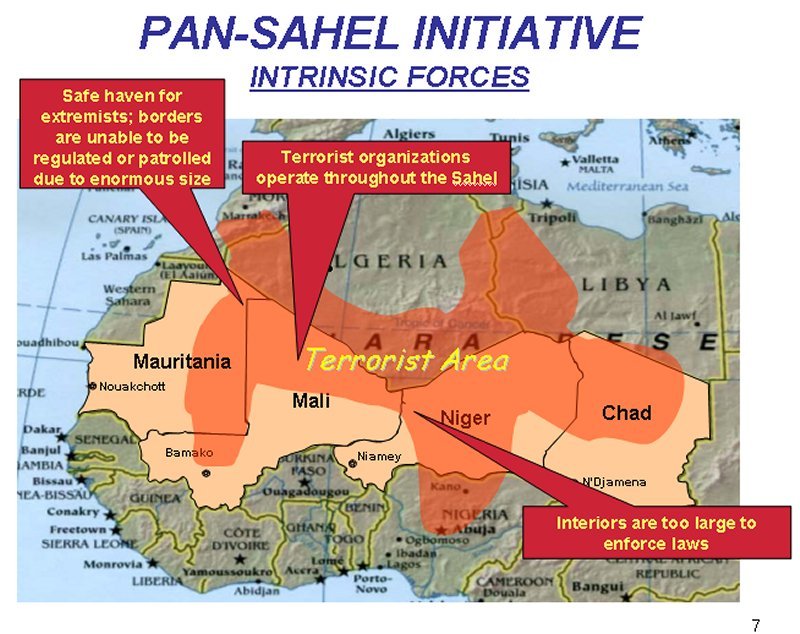

A general idea of where terrorist activity is the greatest threat across Africa (excluding Somalia), although online terrorists can presumably capture followers from any nation. {GlobalSecurity.org}

Of late, the world has turned its eyes on terrorism in Africa. However, most attention has been on Somalia. Somalia certainly stands out in terms of media coverage – and rightfully so. The Islamist extremist group al-Shabaab is now a household name after causing mass casualties in Mogadishu (among other cities) and contributed to epic famine in the Horn of Africa. The lack of a stable government – a direct cause of al-Shabaab’s activity – has contributed to a lawless state, which in turn has contributed to another form of terrorism – piracy on the open seas.

Many individuals don’t realize African terrorists have Internet service and actively use the Internet. Although Somalia hardly had an Internet connection at the turn of the millennium, stated Internet penetration is now around the 1.1% mark (ITU June 2010), with Facebook penetration conservatively estimated at 0.35%. Of course, the number of Internet users is difficult to track as many use proxy IPs and most connections are not private. Fewer than 100 domains are registered to Somalia, but again, this statistic only speaks to a lack of content on Somali-owned sites and not a lack of content by Somalis. Similar trends ring true for Mauritania and most other nations occupying the Sahel.

Despite a general lack of Internet access in these remote, and often landlocked areas, terrorists have found the means to gain support and claim new followers in online forums. The nations of interior Africa, notably Mauritania and Mali, are known to house significant terrorist factions. Border protection is difficult in remote areas, but Internet protection has proven to be just as difficult. A lack of Internet laws and emphasis on positive tech applications are allowing the terror threat to grow.

Mauritania:

In 2012, the ACE cable will bring Mauritania its first true global broadband services. However, the nation’s Internet laws are not at all ready for the phenomenon. A July 2011 article on Magharebia.com, titled “Jihadist websites tempt Mauritanian boys” sounds foreboding. The article describes how youth in Nouakchott are increasingly turning to Internet cafes to pass the time. The fear is that impressionable and pessimistic youth will lock on to enticing new media promoting extremist views. Cafe owners cannot be relied upon to monitor web habits. Instead, it will take government action to keep the nation safe. Blocking social networks is not the solution, but perhaps limiting certain sites could be viable.

A September 2011 article explains the lack of government ability to ban websites, although the tech capacity certainly exists. Terrorists apparently are using YouTube, but a fine line exists between banning the service completely and filtering its content. Either way, an Internet cafe owner explains how he lost customers after advising them to stop visiting jihadist websites.

Morocco:

Mali’s security services claim al-Qaeda has plans to strengthen its network in Morocco. Last month, three members of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) were arrested. One of the men was an active individual on jihadist Internet sites with links to the al-Qaeda network. A similar dismantling occurred in December 2010. At that time, Morocco devoted a team of experts to pursue terrorist groups operating via the Internet. One analyst called the Internet “a school for terrorists” and pointed out how the web can convey radical messages and also train terorrists to carry-out attacks.

The nation is very aware of terrorists’ intentions to destabilize the region, but policing the eastern and southern borders remains difficult. Hopefully, online monitoring efforts can counter the physical challenges of watching AQIM operatives.

Nigeria:

Boko Haram has been bombing parts of northern Nigeria since 2009. No word on how active the group is online.

Chad, Niger, Mali, Algeria, Libya:

Little definite information readily available on how terrorists are harnessing online means.

A series of hierarchies could ameliorate the terrorist threat in Africa. Under this model, parents would monitor their children, cyber cafe owners would monitor patrons, and ISPs/government would filter the most extreme online activity and promote safe web habits. In more detail:

- Teenagers must be steered in the right direction. Gale Ngakane, correspondent for Botswana’s The Monitor, sums up the sentiment best when she warns, “With Internet access easily available to children at home, school and from Internet cafes, you can never really know what your child is up to. The scenario in Mauritania sounds exactly like many urban areas in the United States. For example, one effective way to curb gang activity is to offer after-school programs for youth. Why can’t at-risk African nations seek funding for tech competitions?

- Governments must block known terrorist websites. Yes, this is blatant censorship, but not all web filtering should be treated equally. A proven life-or-death situation is different than simply attempting to prevent dissent. Social networks should not be entirely blocked, however, which poses a major challenge as terrorist groups begin to rely more on social media and perhaps less on traditional bulletin boards. At-risk nations can consult with other governments and security forces before enforcing any kind of blockage. Additionally, governments should consider public campaigns to raise awareness of the harms of jihadist actions.

- Cyber cafe owners need to be vigilant and choose patriotism over profits. Currently, if an owner denies service to a militant youth, the youth can find Internet access elsewhere. However, if all Internet cafe owners agree to enforce safe web browsing, then the youth will have no choice but to see a private access point.

For now, home access remains extremely limited across the Sahel, as does mobile broadband. However, the arrival of true broadband for Mauritania, Chad, and Niger in 2012 is sure to encourage lower access costs, and therefore, encourage more private Internet use. Dangerous, especially when coupled with streaming video. Now is the chance to foster safe Internet habits. It’s not worth the risk to wait until another attack.

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Pinterest

Pinterest